Cultural Access: A Reflection on Arts Education in Québec

Cultural Access: A Reflection on Arts Education in Québec

By Sarah Turcotte

Illustration: Nicole Kamenovic

This article was written as part of Platform. Platform is an initiative created and driven jointly by the PHI Foundation’s education, curatorial and Visitor Experience teams. Through varied research, creation and mediation activities in which they are invited to explore their own voices and interests, Platform fosters exchanges while acknowledging the Visitor Experience team members’ expertises.

“To democratize, on the one hand, means to be open to the greatest number of people, to make sure that those who typically don’t go to museums actually discover themes that correspond to their own concerns and interests. In other words: democratizing the museum means including forms of cultural expression that were previously excluded from it, therefore attracting new viewers. On the other hand, democratizing also means reaching out to the public and going to collective spaces beyond the museum [1].”

Since the second half of the 20th century, we have witnessed the gradual public opening of museums. These institutions are undergoing a “people-centered shift” that marks their transition from modernity to postmodernity [2]. We have become more and more conscious of community life and our engagement with others has steadily grown, but public funding in the cultural sector remains limited. Recognizing the central importance of visitors while being forced to integrate the marketplace, museums have launched campaigns to democratize art and culture. As a result, the public is now at the centre of museum-based activities. Not only does this involve reaching out to as many people as possible, but also keeping them interested. Art museums willingly lend themselves to projects that can broaden their communities and increase access to museum programs and facilities, namely through the development of different cultural mediation strategies.

After several years of concrete action and reflection, it is worthwhile to look at how efforts to democratize the arts, culture and museums in Quebec have played out. Are artistic and cultural venues or content more accessible today? If so, to whom does this accessibility apply?

According to the most recent survey on the cultural practices of Quebecers carried out by the Ministère de la Culture et des Communications (MCC), art museum goers were by and large educated and wealthy [4]. First, the 2014 data indicates that the majority of visitors have at least a college diploma (DEC) and many even have a university degree. Second, a correlation can be found between the number of visits and income: the higher people’s financial means the more frequently they attend museums throughout the year. For its part, the demographic data on the population of Quebec for 2015 reveals that 50% of households have annual incomes of $60,000 or more [5]. As for education levels in Quebec, in 2016, 48% of individuals between the ages of 25 and 64 have at least a college diploma, while 29% have a university degree.

While this data shows that many Quebecers have a certain level of education and financial security, the MCC’s survey also reveals that only 18% of these households stated they visit an art museum either a few times a year, about once a month, or at least once a week. Furthermore, if we look at the data on households with an annual income of at least $60,000, we notice that only 22% attend art institutions several times a year. In other words, nearly 4 out of 5 families in Quebec with incomes that are higher than the median never, or rarely, go to art museums. All in all, one may question the effectiveness of these accessibility measures if even a majority of relatively educated and wealthy Quebecers do not necessarily visit art museums.

Generally speaking, we could link the notion of accessibility to cost, proximity, or even to how public places and content are adapted to people with particular needs. This might include, for example, elevator access for people with reduced mobility or audio-guides. We might also consider public transit options, opening hours, languages used, the availability of a coat-check, parking, rest areas or family zones, etc. In an art museum context, considering the abstract nature of some exhibitions, accessibility also comes down to the ability to understand the artist’s vision or to decipher or even relate to the cultural content. Consequently, audiences with sufficient financial capital and educational levels would likely be able to navigate any accessibility challenges. In other words, they would have the ability to travel to the venue, pay for any transportation costs and admission fees, understand and interpret the works, etc. Given this, one wonders why even the people for whom the art museum is most accessible do not visit it, or only rarely so.

Several theories can be put forward. Namely, we might think of omnivorism, the competing markets of the culture and leisure industries, or the limited free time when work and family obligations occupy most hours of the day. It’s interesting, however, to consider the idea of information and interest: are Quebecers aware of museum-based activities and do they want to visit art museums? How does culture fit into the daily lives of citizens?

As sociologist Jean-Marie Lafortune notes, cultural mediation is developed within the three sectors of public policy intervention: either for the democratization of culture, cultural democracy, and art education. The questions raised here specifically involve a discussion about art education. According to this researcher, this is sustained by “the stakeholders of formal and informal education,” and it answers three objectives: “to allow students, but more broadly all citizens, to build a rich personal culture during their educational years and throughout their lives; to develop and strengthen their artistic practices; to introduce them to artists and their works, as well as cultural venues [6]”. But the question remains: is the educational relationship between Quebecers and culture nurtured enough to create a genuine interest in art museums, or at least, for citizens to know about these institutions?

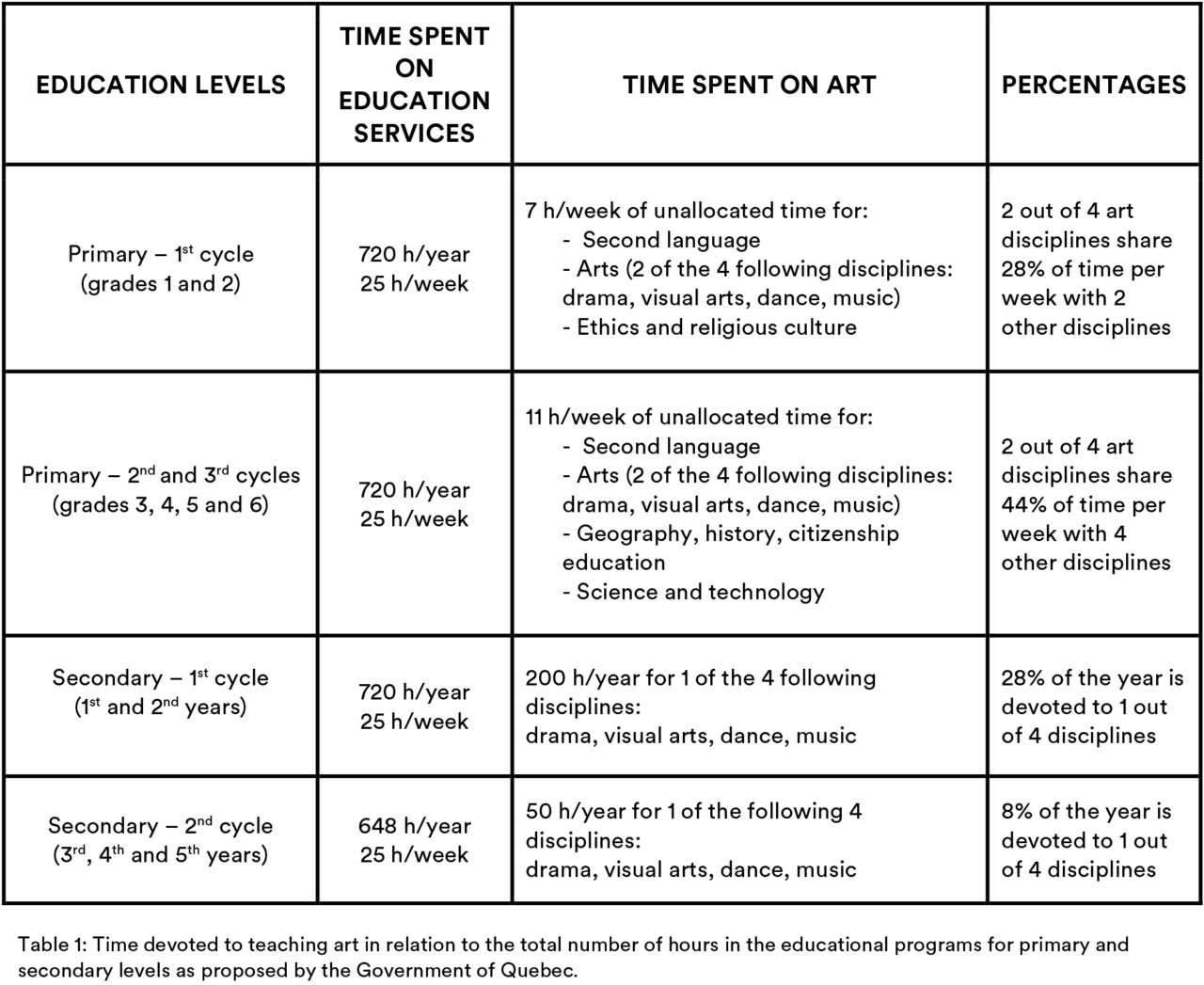

The Government of Quebec’s Loi sur l’instruction publique (Education Act) indicates the amount of time that must be allotted to various educational activities and the distribution of hours among different disciplines. Within the pedagogical system of preschool education, and primary and secondary school teaching, overall, we note that the amount of time devoted to the arts represents only a small percentage of activities within the entire educational program. Additionally, depending on their level of study, students may only select courses from one or two general artistic disciplines, either drama, visual arts, dance, or music (see table 1) [7].

It should be noted that for secondary 3, 4 and 5 students, only 8% of the school year is dedicated to 1 of 4 arts disciplines on offer. However, it is well-known that adolescence represents a crucial period in the development of an individual’s identity [8], and by the same token, in the defining of their tastes. It’s a period of tremendous change, learning and self-discovery. What’s more, courses in the visual arts, drama, music and dance focus more on production than reception. Far more time is spent learning techniques than analysing and interpreting existing works: we want students to learn how to paint or to play an instrument rather than look at a painting or listen to music. Furthermore, among all students in Quebec’s public education system—from preschool to secondary school—only 14% attended an art museum in 2019 as part of a school activity [9][10]. How can students develop knowledge or interest in museums and art institutions when their exposure to these environments is so limited? How can educational structures spark their curiosity about art and culture? Does the fact that, from day one, the arts are considered a specialty in isolation from the general curriculum contribute to their marginalization in society?

This reflection is by no means comprehensive. In fact, it would be relevant to examine the data on art education within the private school sector as well. We could also look at other areas that aren’t necessarily part of formal education but are routinely encountered by the public as a way to understand their relationship to arts and culture and their influence on the general population. For example, art interventions in public space or cultural content broadcast on television and radio. Finally, in addition to art museums, it would be fair to look at attendance figures in other cultural institutions as commercial and university art galleries or cultural and exhibition centers. Nonetheless, the data presented here illustrates that art education is, on some levels, rather limited in Quebec’s public school system although we now know that cultural institutions have a positive impact in society. A recent study by Oxford Economics illustrates the value and benefits of GLAM (galleries, libraries, archives and museums) in Canada: the results confirm that these institutions greatly contribute to the economic health of the country as well as the health of all citizens, in addition to being important engines for social and pedagogical development [11]. Therefore, increasing investment in the education and promotion of arts and culture seems like a wise choice for Quebec.

While the implementation of a variety of cultural mediation tools over the past few decades has allowed a wide range of individuals to attend art museums, regular visitors are still primarily part of the social and intellectual elite. It should also be noted that encounters with artistic spheres is limited, even within these privileged groups of Quebec society. And so, beyond questions around accessibility and the artworks themselves, it’s possible that a lack of information or interest is an ongoing issue in the campaign to democratize culture. The relationship between citizens and art museums seems to be built and strengthened by art education. However, its limitations within Quebec’s public school programs can be a contributing factor in the ongoing disconnect between the public and museums. Therefore, not only is it a matter of promoting the arts and culture among Quebecers, but also of rethinking and reviewing pedagogical approaches to formal education establishments. Public schools and cultural policies, inevitably, play a major role in this issue, but what about galleries, art centers and museums? Should they step up their efforts to attract bigger audiences or go directly to where the people are, beyond the museum’s walls? A pilot project was recently launched by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts that allows students to attend some of their classes on site at the Museum, in proximity with the works on view. This initiative inevitably helps to create strong, lasting ties between individuals, the museum, the arts and the cultural landscape as a whole.

Nevertheless, unequal representation of social and cultural diversity in art museums, and the historically exclusive reputation these institutions carry today, also certainly influence the level of interest people have in them. How can Quebecers be more drawn to and engaged with institutions that have been known for being closed-minded and arbitrary? The work lies not only in the putting Quebecers in touch with arts and culture, but also in the very structure of museums and art institutions themselves: we must deconstruct our biases and adopt appropriate practices that support the democracy of cultures, allow each person to recognize themselves in these cultural institutions and reflect true social justice.

Note

All quotes in this article have been translated from French to English. Please note that the expression “cultural mediation” is usually used in French literature as “médiation culturelle”.

About the Author

Sarah Turcotte is a PhD student in museology, mediation, heritage at the Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) and is interested in current issues of cultural democratization. She more particularly explores the tensions between the educational, social and corporate missions in the identity construction of art and contemporary art museums in the 21st century, deepening the notions of mediation and media coverage of culture. In addition to her studies, Sarah is part of the Visitor Experience team at the PHI Foundation for Contemporary Art and continuously works on several research projects, notably within the Groupe de recherche sur l’éducation et les musées (GREM), which allow her to contribute to various scientific publications and conferences.

Bibliography

[1] Schiele, B. (2018). Des fourmis, des papillons, des poissons, des sauterelles aux prises avec deux ethnologues de l’exposition. Note sur Ethnographie de l’exposition. Communication & langages, 196(2), 55‑72. Cairn.info. https://doi.org/10.3917/comla1.196.0055

[2] Montpetit, R. (2002). Les musées, générateurs d’un patrimoine pour aujourd’hui: Quelques réflexions sur les musées dans nos sociétés postmodernes. Dans B. Schiele, Patrimoines et identités (p. 77‑117). Éditions Multimondes.

[3] Aboudrar, B. N., & Mairesse, F. (2016). La médiation culturelle. Presses universitaires de France; Cairn.info. https://www.cairn.info/la-mediation-culturelle--9782130732549.htm

[4] Simard, S., Anctil, M.-H., Magnan, S., & Ministère de la culture et des communications (2012- ). (2016). Les pratiques culturelles au Québec en 2014: Recueil statistique. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. http://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/2576641

[5] Gouvernement du Canada. (2020). Tableaux de données, Recensement de 2016. Statistique Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/dt-td/index-fra.cfm

[6] Lafortune, J.-M. (2017). (Dé)politisation de la culture et transformation des modes d’intervention. Dans Expériences critiques de la médiation culturelle (p. 31‑54). Presses de l’Université Laval.

[7] Régime pédagogique de l’éducation préscolaire, de l’enseignement primaire et de l’enseignement secondaire, RLRQ c I-13.3, r. 8 (2020). http://www.legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/fr/ShowDoc/cr/I-13.3,%20r.%208#se:22

[8] Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton.

[9] Institut de la statistique du Québec. (2020). Fréquentation des institutions muséales répondantes selon le type d’institution, données trimestrielles et annuelles, Québec. Institut de la statistique du Québec. https://statistique.quebec.ca/fr/produit/tableau/frequentation-institutions-museales-repondantes-donnees-trimestrielles-et-annuelles-quebec#tri_temps=19602810000

[10] Gambarin, A., Lukins, S., & Tessler, A. (2019). Étude sur la valeur des GLAM au Canada. Oxford Economics. https://museums.ca/site/reportsandpublications/studyglamscanada2020?language=fr_FR

[11] Ministère de l’Éducation et de l’Enseignement supérieur. (2020). Prévisions de l’effectif étudiant au préscolaire, au primaire et au secondaire pour l’ensemble du Québec. Gouvernement du Québec. http://www.education.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/site_web/documents/PSG/statistiques_info_decisionnelle/Previsions-provinciales-2020.pdf