Interview with Reina Lewis

Interview with Reina Lewis

Interview with Reina Lewis

By Emily Keenlyside – DHC/ART Education

Faith and Fashion: Religion, Dress and Politics

Emily Keenlyside: Thanks for taking the time for an interview today. I’d like to start by talking more broadly about the research surrounding your collaboration with DHC/ART, and then go back to Wednesday’s Faith and Fashion: Religion, Dress and Politics, the round table event chaired by yourself, and comprising panelists Farheen HaQ, Yasmin Jiwani, Cheryl Sim, and Jasmine Zine.

The title of your most recent book is Muslim Fashion: Contemporary Style Cultures. For those less familiar with your area of research, could you define the term Muslim fashion?

Reina Lewis: I chose to call the book Muslim Fashion rather than, for example, Islamic Fashion, because although some people in the field - designers, creative entrepreneurs, and some Muslim modest dressers - would refer to Islamic fashion, I prefer the term Muslim fashion because it doesn’t seek to define what is or what is not Islamic, or “properly” religious. Muslim fashion is an intrinsically complex term because of course Muslim women have been looking fashionable in all sorts of ways for generations and generations all around the world. So I’m talking particularly about Muslim modest fashion in the contemporary context. And within that, there are lots of different ways of understanding modest fashion. So we’ll talk about that a little bit later.

I chose Muslim fashion because it gives the widest possible frame. Sarah Joseph, who was the editor of Emel, the British Muslim lifestyle magazine said ‘there’s one Islam and lots of Muslims’, and I think that’s a really useful way of understanding it: I’m not seeking to demarcate what is the best form of modest dressing – or if indeed of any form is required. And that goes for Muslims or any other religious group. Some people use Islamic fashion to brand their product, and therefore I would refer to them as an Islamic fashion brand if I were referring to that particular brand. But I wanted to open it up quite broadly.

EK: As a cultural studies researcher, you investigate practices of devotion; how they unfold in the fashion world, and the everyday practices and gestures of (mostly young) Muslim women as they engage with it. How are the frameworks offered by this discipline of particular use to you?

RL: I came to cultural studies from feminist art history and literature. I used to write about dead people and their books, or dead people and their paintings, with a few forays into live human subjects when I was looking at mostly lesbian, gay, and queer artists and writers. This project meant looking at live human subjects and what they design, sell, wear, write about, and talk about. And so I’ve moved more into sociological approaches whilst also retaining a focus on texts and representations. For example, one of the chapters in my book looks at Muslim lifestyle media, the print magazines that started in the mid 2000s, and also at the growing field of blogs and all social media channels. Of course I talk about the images and the texts, but I also wanted to talk about how they get made. So for example, if you’re a Muslim lifestyle magazine, and you’re having a fashion editorial, how do you recruit models, how do you get models not to do industry standard, super sexy poses if that’s not what you want? How do you liaise with mainstream fashion brands to persuade them to let you call in products to use in the shoot?

Interviewing people, one of the frames that I found useful from sociology was looking at everyday religion. An everyday religion approach provides a helpful frame for thinking about religious practices in the broader sense: not just about worshiping in a church, or indeed belonging to a church, but about the way in which people achieve their religiously related, or spiritually related, self-actualization. And dress and the body is one form of that. This approach allows you to think about religious practice as part of the everyday, as often linked to the market, not as oppositional to it; as linked to the body, not separate from it (of course some religions would see it as more separate, others don’t); and as changeable and syncretic. So for example, you might be an observant modern orthodox Jewish woman who also does Buddhist meditation. Does that mean you’re a bad Jew? Does that mean you’re trying to be a Buddhist? Or does that mean it’s part to normal life, that you mix these things up? Also, religious practices change over time; in a generic and collective sense, but they also change over the course of an individual’s lifespan. Partly to do with the predictable phases of life: getting older, maybe having children, maybe experiencing bereavement, etc. but also to do with macro political and social changes.

An everyday religion approach is also a way of getting out of the trap of trying to judge what is a good or correct form of modest fashion. Which politically I don’t want to do, but this is also a good way to frame that by saying because someone is wearing hijab one day this way, and then wearing it another way another day, that doesn’t invalidate it. In fact, if they wear hijab sometimes but not all the time, that doesn’t invalidate it. So it’s been very helpful.

The other reason why cultural studies and sociological approaches to religion are helpful is in the classroom. If I’m teaching postcolonial studies, doing a session on the veil (historically, maybe in art history, also in the contemporary context), in my classroom I can have Muslim women who cover, Muslim women who don’t, Muslim men who come from families where some or all of the women cover, and Muslim men who come from families where no one does. I can have people of different religions and of none, and of different ethnicities. My job as the educator is to say in my classroom we have a multiple interpretation framework for these things. And inevitably there will be somebody who says ‘well the Koran says…’, or ‘Allah requires that we do such and such’, and it’s my job to say that’s one interpretation. I would always argue that all religious interpretations are historically contingent, spatially located, and change over time. In this classroom, or in this discussion, we accept multiple interpretations. And that’s partly my job as the educator, or the convener, so that other people, other co-religionists, don’t feel that they are being judged as a bad Muslim or a bad Jew. So that’s my responsibility.

EK: So to recognize those subjective experiences or perspectives as a starting point.

RL: And to validate them. To say this is not right or wrong. I’m not a theologian and I’m not interested in arbitrating if this is a better way or a worse way. In fact sometimes when there are apparent contradictions, that’s something very interesting to think about, because we are all contradictory.

EK: I’m very interested in these contradictions; reading prior to and following last evening’s event, I was reflecting on the distinction between ‘modest dress’ and ‘modest fashion’, and the deliberate use of the term ‘fashion’ over ‘dress’. And as you mentioned briefly, how young women of myriad faiths are challenging the perspective (and I imagine this could come from outside and within their respective communities) that ‘modest’ and ‘fashion’ are incongruent.

RL: Yes. As I said, women of many religions have been dressing with modesty in mind, or in accordance with community convention for generations. What’s different now, is that many women are styling modesty through participation in mainstream consumer cultures, and in this case specifically, the mainstream fashion industry. So modest fashion, in this context, is also a loose, inclusive term that refers to a niche market, and to a field of fashion mediation. The Internet was essential in allowing commerce and commentary to develop. The Internet lets you do a business start-up with less risk; it’s cheaper, it’s easier. Modest fashion was one niche sector that emerged online. At the same time as it emerged online, at exactly the same time, you get blogs. In the old days, i.e. 2006-2007, it was blogs, then YouTube, then Tumblr. Through every social media platform, modest fashion has been there. So the modest fashion blogosphere, and we use that category to include all social media, developed at the same time as fashion blogging generically, and followed the same routes across the different platforms – although this is very rarely recognized.

The other thing that the Internet did was foster dialogue and connections across and between faiths, and within different elements of the same faith. I did a project that was funded by the British funding councils with Emma Tarlo, who is professor of anthropology at Goldsmiths College, and we looked at faith-based fashion and Internet retail. Our hypothesis was that the Internet was allowing start-ups to begin, most of the starts ups were led by people from faith communities, generally women who couldn’t get what they wanted in stores, or what they wanted for their daughters, and they were motivated to provide clothes for women in their community. So we wanted to know, are they getting consumers from other faith groups? Because if what you need is a maxi skirt that isn’t transparent and that doesn’t have a slit to the thigh, you might be Jewish, you might be Christian, you might be Muslim. And what we discovered was the entrepreneurs did get consumers from other faith groups and yes, they did welcome it. Sometimes they were willing to expand their range or change their offering to accommodate that.

At the same time, blogs were developing; we could see the comment streams were coming, and people would say ‘I’m not Muslim but I really like this’, or ‘I’m Jewish, and I like your Muslim fashion blog’, or ‘I’m Muslim and I’m following your Jewish fashion blog’, etc. And then some of the key bloggers who became famous within the sector would cross post. So some women would refer to a modest fashion “movement”, because they get comfort and solidarity from people from other religious backgrounds, who are also engaging in modest fashion, and who face some of the same challenges as they do. Of course, what women of different faiths might feel is required could be distinctive, and there are different interpretations within faiths, so this cross-faith dialogue is not without contention, both intra faith and extra faith.

The other thing that’s important is that the Internet allows the dialogue to expand beyond the merely fashionable. So I feel quite strongly that modest fashion is a conduit for wider discussions about women’s roles and also women’s empowerment. So for example, commercial websites in the early days would also have links to stories of social relevance, or a hijab fashion blog would have links to stories about attempts in France to ban the hijab. The other thing that happens is women discuss their roles. They might discuss family, education, or limitations and opportunities that they encounter. And there is now a proliferating set of offline events as well. So around the world, you’ll find modest fashion shows - sometimes cross-faith, but more often single faith - Muslim fashions shows that are a chance for people to meet up and talk to each other, for entrepreneurs to show their store. And they are often very directly linked to women’s social empowerment. So they might have motivational speakers offering guidance on how to move into higher education, career advisors, etc.

EK: So there’s a real leadership element to it.

RL: Absolutely. And often these are women-only events, or sections of it will be women only, so women will often feel like they can speak more freely.

EK: This question of empowerment leads me to the question of the active participation found online, vloggers who haven’t necessarily seen themselves represented, so they are representing themselves.

RL: Yes. And I think that comes back to the discussion last night about not seeing Muslim women as victims, or indeed women of other religious persuasions, and agency, and trying to make change. One of my arguments that I’m going to be pursuing for my next research project is that many of these young women have developed as role models -- I think that might be the term people would use. They wouldn’t necessarily see themselves as leaders, or say they seek to be leaders, and they would probably certainly not say they are trying to be a religious authority or leader. Now I think, and I mention this briefly in the book, that they are engaged in forms of religious interpretation, and that what we are seeing online are new forms of religious interpretation and practice which are transmitted laterally, peer to peer, and offline as well, and are outside the sometimes vertical lines of traditional religious knowledge formation. So it’s a different form of religious production and a different mode of religious knowledge transmission.

I think that it’s really important that these young women - and now not so young women - be seen as influencers. I’ve been looking at this for a little over ten years, so the women I was talking to were broadly 18-28, plus a few years. So now they’re 28-38, up to 43-44, and there is another gang of teenagers coming up. So in my new research I’m interested to see, as these women move through the stages of adult life and out of young adulthood, if the knowledge and the status that they have within the modest fashion sphere is going to translate as a form of cultural capital, spiritual capital, social capital, into adult roles. So are they going to move into roles of leadership within religious communities, as community representatives, in professional life, in politics, etc.?

People often say to me, ‘what are your tips for brands, what should they be doing?’ and I say these young women are going to need clothes as they move through their lives. There are still going to be students and young moms, and 20-year-olds; but actually, when they are a high court judge, what are they going to wear?

EK: Likely something stylish, but a different articulation of their personal style — not the mainstream, high street fashion.

RL: Exactly. In fact some of the data I have from some of the women I’ve interviewed more than once, would be reflecting on the fact that ‘I can’t shop at such and such store anymore’, or ‘when I was 17, I used to shop in X, but now I don’t’. I think that in terms of presentation, shopping opportunities, and how they style themselves, women who are dressing with religion in mind face their particular version of the generic challenges that all women face. So how do you look more serious, but still a bit stylish? If we think of the 1980s, we have the first women execs to get into the board room, their power dressing was a way to have this kind of virile, masculinized look, but still with some femininity. Women who are breaking boundaries, or breaking conventions, always struggle to find a wardrobe solution, and so new things will emerge.

I was once interviewing a woman who is a senior civil servant in one of the British government departments and she wears high-end clothes, she earns her own money, she likes to buy clothes like many other professional women in their 30s, and she wears a headscarf. She wears hers in the Arab style, a shayla, one of the oblong silk or crepe scarves. She was saying that she does face discrimination, ignorance, and prejudice, and she’s noticed that if she’s wearing colours, or a floral scarf, there is a little less hostility that if she is wearing black. And she was talking to me in my office at London College of Fashion, and she said, ‘this scarf (she was wearing a black silk scarf), this is (she named one of the global luxury brands), it’s really good quality – but no one sees it as that.’ And it was interesting because on her, that black scarf did not register as a colour - which, as anyone in fashion knows, black is a key fashion colour - and I laughed, because she was sitting there wearing all black, and I was sitting there wearing all black. We were both fashionably dressed professional women, but her scarf - the signification of the hijab - overrode the fashion signification of the colour.

So how do you encourage minority religious or minority ethnic women to have positions of power; there is no reason why a sari or a salwar kameez should not be recognized as business dress. Why should you not be able able to wear clothing conventional to different communities as appropriate business wear? It’s partly because who else is going to be in the room or at the interview who will recognize that you are wearing a businessy-looking salwar kameez and not dressed up to go to a party? Not everybody has the cultural competency to understand the different dress codes. In the same way, if I went to speak to a group of men in banking, I wouldn’t necessarily know that the three button cuff was much classier than the one button cuff, or whichever way it was going at that time. I’m not equipped… those nuances, those micro signifiers.

EK: A point that was raised by a few of the panelists last evening, and you spoke to it in your introduction, is what you refer to as the ‘rescue narrative’. We’ve been talking about influence, participation, and empowerment, which really speak to young women’s challenging of this narrative. Is there anything else you’d like to say about that?

RL: The new book is about Muslim fashion and my previous, edited book Modest Fashion: Styling Bodies, Mediating Faith, was about modest fashion, looking particularly in the three Abrahamic faiths: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Young Sikh women and Sikh men are doing modest fashion and starting up companies, doing interesting design that will accommodate religious and religio-ethnic requirements as interpreted. But at the moment, it is Muslims who are facing the most difficult stereotypes. Stereotypes about young Muslim men are about jihadization, radicalization, and potential extremism. Young Muslim women, particularly women who make themselves visible as Muslim by wearing hijab, almost universally experience people assuming that they’ve been compelled to dress this way by local patriarchies. And of course there are Muslim women of all ages in Britain, in Canada, in Muslim minority countries who have little or no choice about when, if, or how to cover. There are Muslim women living in Muslim majority countries like Saudi Arabia or Iran where the state compels them to dress in a certain way. And then are various forms of accommodation or resistance to that.

But there is clearly a cohort of young and youngish women who are able to exercise choice and who argue very powerfully that this is something that they choose to do, and that this choice is an individual human right. That choice, the freedom of religious expression, is a universal human right. And in making that argument they are, as Leila Ahmed has argued, very much a product of having grown up in a Liberal western democracy, and like everyone else of their generation, they are committed to an ideal of liberal human rights (and we might think another time about the inherent contradictions within the liberal human rights framework).

And so after 911 we see a civilizational discourse in which Islam and Muslims are presented as inherently different to the West, and outside of Western modernity. We see a securitizing framework that sees Muslims as a potential threat to so-called Western modernity, as if they are not themselves part of the West, part of modernity, and also under threat from terrorists and criminals. And young women tell me that they understand choosing as essential to why they are wearing hijab. For some women it’s a religious commitment, or spiritual, for some it’s social. For some it’s a riposte to those stereotypes; they want to take the thing that is stigmatizing and use style to challenge that. And some young women tell me very clearly that they use fashion as a way to communicate to external, non-Muslim observers that they are part of modern British, or Western life. And I think this is a very important element of how they are using it.

EK: For my final question I’d like to return to last night’s discussion. Farheen HaQ located her art practice in a movement of contemporary artists using their own bodies as a starting point to examine identity, power, and resistance. She also described how embodied experience is textured and bound by social codes, and that culture inhabits our bodies. And so to wrap up, how could we summarize Muslim fashion in light of what Jasmine Zine made reference to in a similar vein: the body as a cultural text?

RL: There was some great overlap and extension of arguments across the different contributions last night that really drew out some rich veins of thought for further discussion. I think Jasmine is right, and I think Farheen is absolutely right. Many young women that I’ve spoken to certainly tell me that they do give thought to how their body will be read. We know that when we get dressed in the morning we can’t control how we’re going to be read, and that all images are polysemy, read in different ways by different people.

One of the things that really intrigues me is the research that I’ve done with women who have stopped dressing in some of the most spectacular ways. We can think about how wearing hijab, makes you particularly conspicuous as Muslim in certain ways, and if you are styling that fashionably, you’re able to interject that Muslims can be fashionable, part of modern life, etc. — that’s one intervention. Another is women who have stopped wearing hijab i.e. women who did choose to wear hijab and then came to the conclusion that they didn't need to anymore, or they didn’t want to. Sometimes women stop because they can’t cope with prejudice; sometimes women stop because they’ve consulted the scholarly texts and different interpretations, and come to the conclusion that it’s not a requirement.

EK: Again, this evolving, changing expression of our selves and our faith.

RL: Yes, exactly. Within this cohort of women who chose hijab in these ways, in this period, there are increasing numbers of women who are ‘dejabis’, who have ‘dejabbed’, who have consciously removed it. There is also the parallel group of modern orthodox Jewish women who have stopped wearing hats, wigs, or wraps, or whatever means they were using, and that radically changes the way they are viewed in the world and the way that they position themselves. Whilst in some cases it means you get less of an onslaught of prejudice and criticism, and that can be welcome, it can also produce some very disconcerting changes. Many times women still want to be read as Muslim or as Jewish and then they become invisibilized. It also changes the way other elements of their social self are read. So Muslim women who’ve stopped wearing hijab will sometimes say to me that their ethnicity now reads differently, because the colour of their skin, which is marking them out, then disappears. Or if you are Caucasian and Muslim and you stop covering your hair, do you just look like any other white women? The ‘world’, inadvertently, is going to see you as non-Muslim.

It’s also about the many different ways which dressing modestly can be seen as an intervention into different frames; not just with religion but also gender, respectability, class, and so on. I’ve spoken to several modern orthodox Jewish women who have stopped covering their hair who face comparable experiences and presentational dilemmas. Jacqueline Nichols, an artist based in London, wrote on her blog about her experience of the change [1]. When Jacqueline did cover her hair, she was very innovative and stylish in the way that she did it, wearing also sorts of hats, turbans, or wraps. And she would often pair it with trousers, which some modern orthodox women would not wear, and indeed which in some spaces, would be very much discouraged from wearing. And her body management was different. So when she’s not covering her hair, wearing the trousers doesn’t appear to be insurrectionary.

So there are all these different nuances of what that means, so when we think about the body as a cultural text, the clothes are part of how we understand ourselves. I think of Saba Mahmood’s argument about women in the early piety movements in Egypt, that the repeated wearing of the hijab is part of the cultivation of the pious disposition, in the creation of the pious self. It’s not just that you are pious and then you put the wrap on; doing it is part of the disciplining and the learning of the disposition. So then when you don't do it, that also changes the way that you are in the world. And I think that issue of being invisibilized is really interesting.

EK: Similar to way that we understand identity and racialization, I’m picking up on your use of the term invisibilized over invisible.

RL: Yes, in the same way that race or ethnicity will register in different ways. Sometimes people will realize that I’m Jewish because they’ll pick up on some of my more conventional Ashkenazi body management and behaviours, other times people won’t realize it. I grew up in a very big Jewish community where there were lots of different types of Jews and then I went away to college, and for the first time encountered people that hadn’t met a Jew before or, as I would say, hadn’t knowingly met a Jew before. And they would say to me ‘Oh, are you American?’ and I would say ‘No, you’re thinking of Rhoda (the 1970s American TV show with a Jewish protagonist played by Valerie Harper). I’m too pushy, I’m too loud, I gesticulate, I occupy space, I don’t seem terribly British or English (though obviously I’m terribly English in other ways). You’re thinking I’m an American whereas actually what you’re trying to think is, is she Jewish? But you don’t have the frame to make that distinction. Or, as a femme lesbian, when I walk down the road, that’s not necessarily self-evident to people. It probably was in the 80s, when I had really short hair and Doc Martens. It is if I walk down the road with my butch girlfriend. But on my own, it’s the invisibility of the femme. Then we might think about current debates about the trans body. So in a way, the body as a cultural text refers to all these different modes of social stratification and change. But in some cases, there are more risks to getting it wrong or to being visible in certain ways.

EK: Thank you so much for your time.

[1] http://www.drawyomi.blogspot.co.uk/2015/12/goodbye-sotah.html

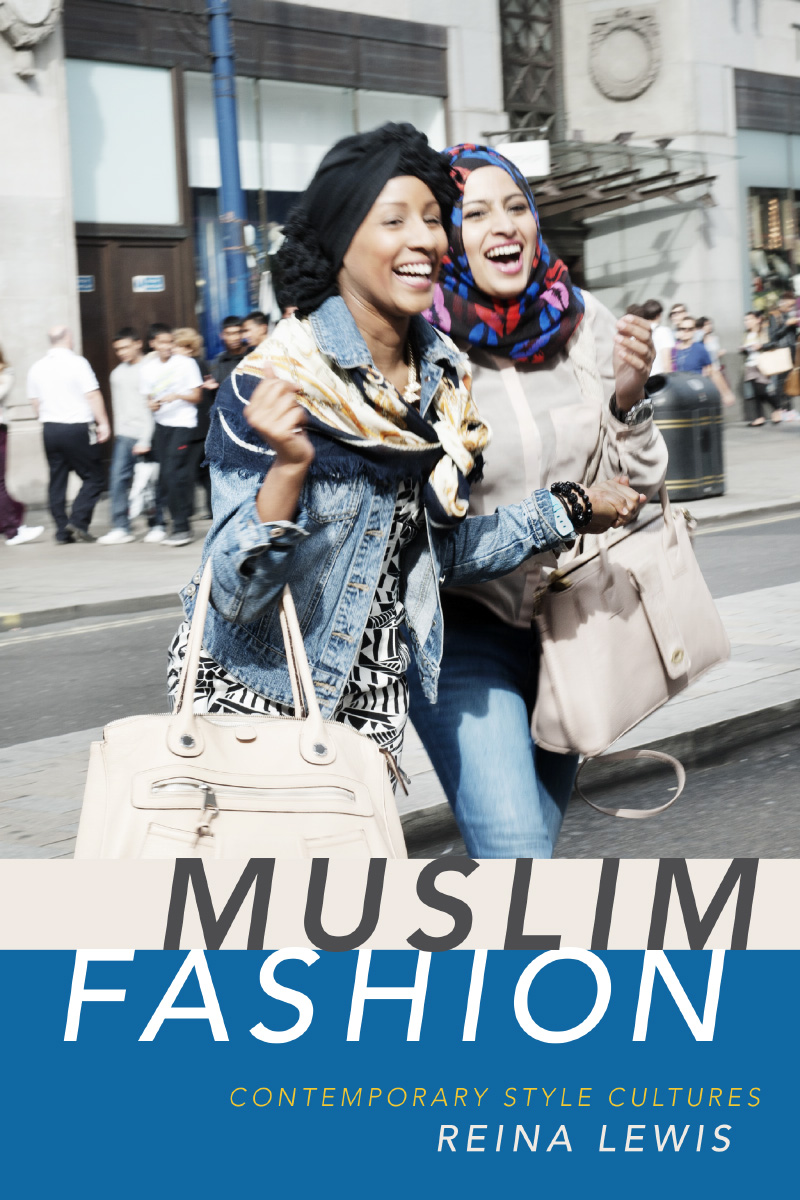

Photo: Reina Lewis, Muslim Fashion: Contemporary Style Cultures. Courtesy of Duke University Press, 2015.